Documentaries tend to have a rather staid approach: force a story via narration, dramatize it with talking heads, and then sprinkle the snippets of primary sources you’ve managed to collect. This is especially common when the subject matter is done and gone. HBO’s newest dredging of rock’s past explores the fascinating celebrity of the man who hated it, eschewing the dusty approach by using personal footage and artwork obtained from the family. The result is, as the title states, a montage of the moods and attitudes that rode Cobain from petulant teenager to superstar to withering junkie. The effect is not dissimilar to reading the published collection of Cobain’s journals (some of which are used in the film), which document song origins and thoughts without a unifying framework. Even though the ending can’t change, Montage of Heck reveals some unexpected context for the last great counterculture symbol, a man who was loved for hating capitalism and comfort, a touchstone for generations of us who felt like he was describing something impossibly personal with his songs.

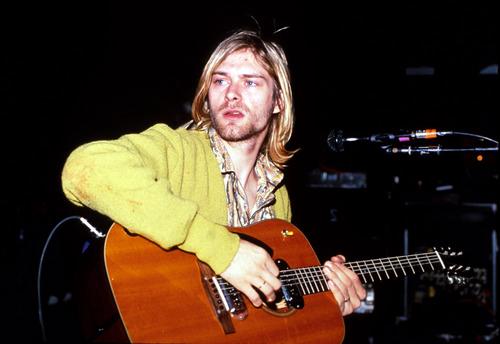

Montage of Heck begins with family footage of a young Cobain being hyperactive and charismatic. A normal kid in boring Aberdeen, nothing seems abnormal. Both the audience and Cobain’s parents sift through this early footage and drawings for clues of the man to come, but the obvious origins appear in his teenage years with his parent’s divorce. It’s a rift he never gets over, moving from house to house without finding a home, turning those feeling into aggression. Footage from this time is somewhat rare but at one point we find him standing on a beach in a jean jacket, hair just starting to grow out, a skinny teenager that could still go either way. Cobain decided to go deeper, settling on antipathy for his surroundings and wasting time with the weirdoes. A few of his drawings showcase his defining lurid imagination, art and energy made to make people feel uncomfortable. Lucky for him, grunge happened, and Cobain gets swept up in it shortly before the wave breaks. Early footage of Nirvana is dirty and aggressive, usually shot in houses that it seems the band is trying to tear down. All three of them, but especially Dave Grohl and Ben Novovich, look impossibly young for what is about to happen. Shortly thereafter, the focused attention of a hundred million arrives straight on top of their heads. In a quiet moment just after signing, Cobain returns to his mother’s home and casually blasts their newly minted demo for Nevermind, his first taste of legitimacy and perhaps the last time he we hear about him enjoying it.

Nirvana was immediately compelling, a unification of the hardcore scene and the lingering hippy anti-establishment sensibilities. Millions of teenagers, all disaffected together, bought in and launched Nirvana right through the ceiling overnight. Montage of Heck’s chronology now shows Cobain performing in front of giant sellout crowds and huge festivals, a stark contrast to the garages and bedrooms of minutes before. Everything was achieved in a moment, well beyond their ambitions. The fall follows, but there are certain caveats to Montage of Heck’s portrayal of what happened. The biggest one is Courtney Love, the free spirited blonde who was perhaps more damaged then Cobain. She entered into his life and completely changed it. The early footage of them, hosting drunken parties and enjoying ironic homemaking, suggests he found a harbor within her. She’s also probably introduced him to the career of heroin junkie and reinforced his apathetic behavior. This is a notable contrast for the film, because Love provided most of the footage and copyright passes. Her inclusion in Montage of Heck is essential, but perhaps it clouds things once fame arrives. We never hear from David Grohl in the film, which rumor has it shares antipathy with Love (though the director took credit for this decision). Throughout the film, the talking heads are mostly limited to Love and Cobain’s parents, people who clearly feel guilty about how things ended up. The spin is impossible to measure in Montage of Heck, even in the primary footage of the latter half of the film, which is made up of either MTV clips or home footage with Love and Francis Bean. We never see Cobain without crowds or Love again, so those are the voices that inform the dynamics of his final years.

This is not to say that Love isn’t candid. She appears unwilling to tell outright lies, and though she dances around the drug issue, the footage make it pretty clear the couple was off the deep end. Curated though the footage may be, it still shows the Cobain family as a little too manic, struggling to maintain the divide with the public while issues brewed at home. The arrival of Francis is probably the richest vein in Montage of Heck. Though the violence of the stage persona remains, Cobain’s daughter seems to soften him up. One of the last bits of footage, which was filmed as a tossed off interlude of family life but which comes across as incisive, shows him standing uselessly to the side while Love holds and sings to Frances. It’s an alternative to the image of Cobain crushed by attention and fame. Perhaps even as a superstar, Cobain realized he had more in common with his parents than he had thought.

The truth is, as always, unknowable, but Montage of Heck is a fascinating pastiche of a man who still looms large over music culture. The bounty of footage is joined by additional vignettes that animate some of Cobain’s art, which convey the striking imagery of his life. Cobain was an artist who filled every inch around him with something bizarre, which in turn makes even the long stretches of domestic life documented here fascinating. The directors have done an able job constructing the montage, enhancing where necessary but letting the clips speak for themselves as much as possible. On balance, whatever influence Courtney Love had was probably worth it. It’s a pretty extreme invasion of privacy but there hasn’t really been anyone like him in the time since, which seems to necessitate digging into what’s left, to finally see if all in all is all we are. If nothing else, Kurt Cobain would probably have been amused that we’re still so interested in him, decades later.

3/4

Originally published on Synthetic Error May 19, 2015

Comments

Post a Comment